Personally, I enjoy training in different ways to breathe. Some methods involve soft ultra-slow breathing, others involve heavy breathing for time, some during exercise, and some at rest. What I don’t like is that a lot of methods focus on subjective, qualitative outcomes (feeling better, lower anxiety, etc) rather than objective, qualitative outcomes (something that can be measured).

Another issue is that the training I’ve received tended to focus on mechanisms of breathing and not outcomes. For example, if you wanted to improve the fuel economy of your car, the desired outcome would be better gas milage. To focus on a mechanism would be to say something simple like ‘get better tires’ and you’ll have better milage.

Case in point, this occurred when I was in training for Oxygen Advantage. I learned about the oxygen (O2) disassociation curve. It is an interesting thing about the body: you need carbon dioxide (CO2) to help push O2 out of the blood into the tissue to be used for energy. If you lower CO2 in the body the ph level of your blood goes up, making O2 bond more tightly to the blood. You then have less-accessible O2 for tissue. Since the easiest way to get low CO2 is to hyperventilate through the mouth, nasal breathing is always strongly encouraged so as not to end up with low CO2 by accidentally over-breathing.

This is an example of overemphasis on a mechanism, where everything is presented as hinging on the level of CO2 and how it affects O2 in the blood. Struggling to understand the O2 disassociation curve, I eventually found a great video you can see here. This video radically shifted how I thought about breathing through the mouth during exercise. First, yes, if you breathe bigger mouth or nose, you will let off more CO2 because of a greater volume of breathing. Only knowing what CO2 does in this case makes one concerned about getting enough O2 for exercise, because no one wants to over-breathe. Fortunately, the body has other ways to take care of this! When you do anaerobic exercise, you increase the acidity of the tissue, and that balances off the ph caused by the decrease in CO2. Increasing your body temperature also improves O2 transfer between the blood and tissue, so a good sweat works too.

So now we have one reason to want higher CO2, and two not to worry about accidentally hyperventilating. Let’s go back now to considering mechanisms or outcomes. The goal is to improve athletic performance. To recommend a person ‘breathe through your nose to keep higher CO2’ may or may not make that person a better athlete, but you won’t know until you have a measurable outcome.

I ran a fitness test on myself to compare when I only breathe through my nose versus breathing through my mouth when I feel need to.

Protocol:

Day 1: Ramp test with nasal breathing; and

Day 2: Ramp test with oral breathing.

Since measurable outcomes were the goal I used a metabolic cart to measure my O2, CO2, and heart rate (HR).

| Nasal breathing | Oral breathing | |

| Max HR | 178 | 185 |

| Top Speed | 9.5mph | 10.5mph |

| VO2 Max | 46.6ml/min/kg | 57ml/min/kg |

Note: On Day 1, I failed because I was starting to get tunnel vision, and on Day 2 my leg muscles reached their limit.

My performance with nasal breathing was better than I anticipated. I hit almost the same max HR both days, and only 1mph difference was closer than I thought I would achieve. Unfortunately the good news stopped there. My VO2 max was 22% greater breathing through my mouth, and I did not feel like I was about to lose consciousness doing it! This is important as the more oxygen I can take in, the more energy I can generate.

I also compared how well I recovered after both tests. This table shows calories burned when I hit my max performance for both tests, and what it was after recovering for 3 minutes.

| Nose | Mouth | |

| Calories/min at peak | 18.8 cal/min | 27.5 cal/min |

| Calories/min after 3 min rest | 5.5 cal/min | 8 cal/min |

| Drop in HR after 3 min rest | 176 to 119 | 185 to 123 |

It’s interesting to see here that in both cases my metabolic rate (MBR) dropped by about 70% after a 3 minute rest, so my rate of recovery was consistent. However, my MBR only dropped 13.3 cal/min with nasal breathing, and 19.5cal/min with oral breathing. This tells me that despite peaking higher, the amount of recovery is greater when I breathe through my mouth.

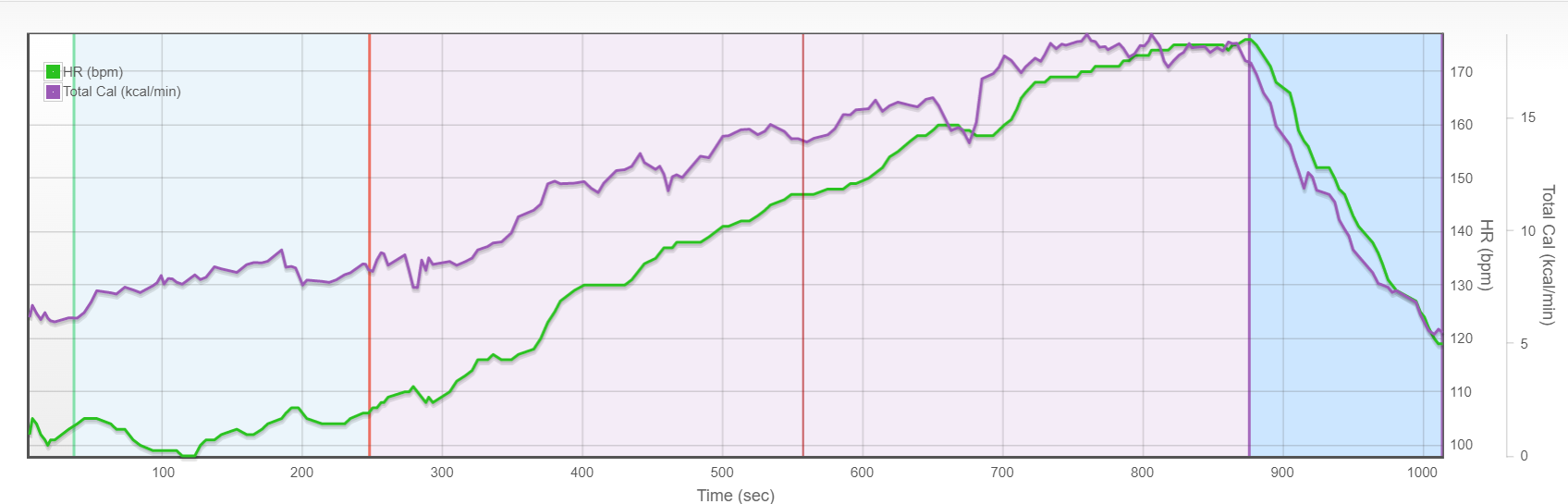

I saw the biggest difference between where I hit my peak performance. When breathing through my nose, I maintained >17.8cal/min for the last 3 minutes of the ramp test (starting at a speed of 8mph). In other words, I plateaued with three minutes left and spent the rest of the time slowly burning out. With oral breathing, the peak, at about 30 seconds before failure while at a speed of 9.8mph, actually looks like a peak. The graphs below show the difference between the nasal breathing plateau and the steady climb to the peak of oral breathing performance.

Nasal breathing – metabolic plateau

Oral breathing – metabolic peak

Returning again to comparing mechanisms and outcomes, if you only know how low CO2 affects the oxygen disassociation curve, you might wrongly conclude there to be a need to always avoid oral breathing. I admit, nasal breathing did better than I thought it would in comparing top speed, rate of recovery, and max heart rate. Where it showed itself to be inferior was in VO2 max and peak energy expenditure. All in all, there was no place where nasal breathing was superior to oral breathing. This contradicts my initial education about the oxygen disassociation curve.

The takeaway here is that we all need to be careful when we hear things like “Do this, and it will make you better.” This is especially true when the information what outcome will improve and how it will improve is lacking. We need to challenge what we think we know, and see if it tests outs. Re-examining old ideas is as important to growth as learning new one. We always get better by learning more.